Night Train to Munich, released in 1940, is set in 1939 amidst the events leading up to when Britain declared war on Germany with the opening scene inside Hitler's mountain retreat. The Fuhrer is yelling orders to his Generals about Austria and the Sudetenland and the film subsequently cuts to images of the German army invading neighbouring countries as they ‘jackboot’ their way across Europe expanding the German Reich. One of these annexed countries is Czechoslovakia where Margaret Lockwood‘s character Anna Bomasch is first seen.

Anna’s father, the inventor Axel Bomasch (played by James Harcourt), flees from Czechoslovakia moments before the German army invade; as an inventor of new armour plating steel, he has been warned that the Germans are looking to take him captive so that he will work for them in helping their war effort. Unfortunately, Anna foolishly spends more time packing clothes and looking for her pet dog than she should have done and is captured and put to work as a nurse in a concentration camp.

In order to get their hands on the inventor the Germans stage-manage a meeting of Anna and undercover agent ‘inmate Karl Marsen’ just as he is being beaten by the guards. Anna naively forms a friendship with the agent revealing who she is. The devious Marsen, played perfectly by Paul von Henreid (as he was then known before dropping the von and moving across the Atlantic and achieving success in Casablanca and other films), also explains his need to escape and with the help of an ‘old friend’, who is now a guard at the camp devises an escape plan which successfully sees them cross Europe to safety in England.

As Anna tries to find her father, she receives a message that will help her telling her to seek out Gus Bennett, a singer and salesman of popular romantic but relatively slushy songs at an unidentified seaside resort on the south coast of England. Enter Rex Harrison in his first major film of his career. Unbeknown to her, Bennett, real name Dicky Randall is also a secret agent working for the British Intelligence. In explaining his alter ego of Gus Bennett he says “Nature endowed me with a gift, and I just accepted it.” “It’s a pity it didn’t endow you with a voice,” she retorts. Was this just acting or was Harrison selected for this role because he couldn’t sing? Either way, his subsequent appearance in the much later film My Fair Lady was to prove that singing was never his forte. Bennett is suspicious of how Anna was able to escape from Germany so easily and rightfully so, when he belatedly realizes that Marsen is a German agent and has succeeded in his plan to get Anna out of Germany in order to find and capture her father and to spirit them both back to his beloved fatherland. Piqued at how easily the German enemy have manged to trace Axel Bomasch and take him prisoner to work on weapons, Bennet seeks permission to put things right and rescue the inventor and his daughter. His superiors refuse him permission due to the high risks involved, but he is informally told that he has some overdue leave with the hint that perhaps he needs to disappear and take a holiday.

Right from the start of Night Train To Munich, it is the naivety of Margaret Lockwood’s character that leads her from crisis to crisis, from being captured by the Germans, her subsequent escape to England led by a German spy and her betrayal of her father by revealing his location to Marsen who subsequently whisks them both back to Germany via U-Boat. It is only at this point in the plot that she starts to realise how foolish she has been and the dangers that she and her father now face.

Cut to Germany where Bomasch and his daughter are being held captive, albeit in the relative luxury of a hotel. Unable to convince them of the merits of working for Germany, the military officers have no option but to hand the two over to the Gestapo where they are to be taken to Munich for further interrogation. However, before they are handed over, Bennett arrives in disguise as a debonair German officer, taking on another persona as he goes undercover as Major Ulrich Herzoff, a high ranking German military engineer. Rex Harrison plays his part with extraordinarily delight and as the film progresses he switches seamlessly between the three characters. Sidney Gilliat, one half of the screenwriting duo Launder and Gilliat, recalled how Harrison jumped at the chance of playing the Pimpernel like character and the opportunity of masquerading as a Nazi officer – uniform, monocle and a hint of cruelty. In typical fashion, he Infiltrates the local German command office and nonchalantly gives the name of another top Nazi as proof of his credentials but is almost thwarted when suspiciously asked ‘But I thought he was doing undercover work in the Balkans?’ ‘And who is not?’ replies Harrison, easily but coolly talking his way through a highly dangerous challenge.

For his part, the undercover English officer tries to convince the German command that he has been ordered to form part of the escorting party with the not-unpleasant ploy of pretending to woo Anna to the German cause. Lockwood’s character plays the part in the undercover rescue reluctantly, perfect in front of the Germans but clearly besmirched about the romantic and personal comments made by Harrison’s narcissistic screen persona. Upon congratulating himself after a close call with a German officer, she retorts “If a woman ever loved you the way you love yourself, it would be one of the great romances of history.” The on-screen relationship between the two stars has developed slightly but not yet to a blossoming romance.

Meanwhile, Charters and Caldicott, the two characters reprised from Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes film, and played by the same actors of Basil Radford and Naunton Wayne, are travelling through Europe as their holiday comes to a close. It is the time of the “Phoney War, the period at the start of World War II that was marked by a lack of major military operations by other Western countries against the German Reich. Whilst the two are aware of military activities in Germany, they do not feel threatened by them, as Britain and Germany are not yet at war with each other. As in The Lady Vanishes, the two chaps are on their way back to England keen to catch the last days of the cricket test match that England are playing in. Boarding the same train as the Bomaschs’ and their military escort, Caldicott thinks that he recognizes Dicky Randall from their school days but the German uniform causes confusion.

Making an unscheduled stop where all passengers have to leave the train, due to it being commandeered by the military for troop deployment, Caldicott grasps the opportunity to innocently greet his old school chum Dicky Randall; on being asked he denies knowing Caldicott or the person he believes him to be, leaving Caldicott confused and Charters mortified with embarrassment. During their prolonged stop at the station they encounter a bossy Station Guard brilliantly played by a young Irene Handl who proudly announces to them that war has been declared and Britain is now at war with Germany. Less concerned about war itself, Charters is worried about recovering a set of golf clubs loaned to an old friend before war makes it impossible to recover them. Whilst trying to make a telephone call to his friend, he interrupts the Gestapo officer speaking with his headquarters and overhears a conversation revealing that the Germans know that Major Herzoff is not who he says he is and that they plan to arrest him.

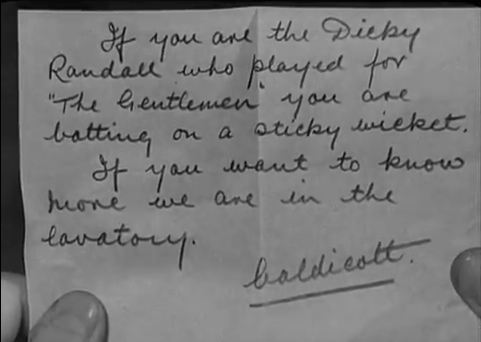

Initially thinking badly of him, for seemingly being part of the German war effort, they now know that Dicky Randall is in fact distrusted by the Germans. Back on the train, they devise a humorous but naive plan to get a message to him and explain what Charters overheard. In true Charters and Caldicott style, they hide the message under a doughnut that a waiter is delivering to the compartment holding the captors and captives.

At this point in the film, the plot picks up pace to become a full blown thriller as the three Englishmen meet clandestinely to hatch a cunning plan to save the day. Initially overpowering the German officers and guards to release Anna and her father, Charters and Caldicott swap their clothes for those of German soldiers in order to carry the plan across the platforms, through the station and beyond to commandeer a waiting military car. The chase to the Swiss boundary is fast paced and action packed, particularly at the unguarded border where a cable car lift stretches between the snow topped mountains. Here the final battle occurs as the Germans catch the fleeing group mid-flight.

Shortage of good news in the early years of the war meant that film makers had to fall back on spy thrillers to entertain cinema-goers – Night Train to Munich is a classic example. Originally titled ‘Gestapo’, Carol Reed considered the original script and plot ‘rather serious’ and felt it ‘wrong to make something so heavy at such a time, so made it more amusing’. Watch out for some classic British comedy lines such as the scene where Lockwood says “I am grateful to be in England where people can be happy and laugh” as she stands between a carping cockney and a sharp-tongued scolding woman. There are plenty more humorous lines, particularly in the dialogue between Charters and Caldicott, such as where Caldicott defends Dicky Randall prior to knowing his true purpose “He used to bowl slow leg breaks. He played for the Gentlemen once. Caught and bowled for the Junior Common Room” “You don’t think he’s working for the Nazis, like that fellow, what’s’ his name?” asks Charters “Traitor? Hardly old man, he played for the Gentlemen” says Caldicott confident in his knowledge of his old college friend’s loyalty and patriotism. Giving the matter a quick thought, particularly regarding his cricketing experience, Charters drily points out, “Only once!”

And political barbs too; “Freedom in Germany is far superior to other countries,” declares a German officer with deliberate irony; “it’s carefully controlled and regulated by the state”

The same writing team of Launder and Gilliat, the presence of Charters and Caldicott and the similarities of the interplay between Rex Harrison and Margaret Lockwood and that of Michael Redgrave and the actress in The Lady Vanishes creates the argument that Night Train To Munich is a prequel to Hitchcock’s 1938 film. The comparison is unjust; Night Train to Munich is deliberately tongue-in-cheek providing a fast paced espionage thriller neatly balanced with hints of romance between Lockwood and Harrisson, more serious moments (the concentration camp episode before the horrors of their true purpose was revealed) all with a generous helping of Nazi-baiting comedy. Night Train To Munich is deliberately light-hearted but it has an edge of urgency and anxiety that wasn’t present in The Lady Vanishes; perhaps an acknowledgement that the enemy being fought was ruthless and well organised.

Night Train to Munich was one of the first British films to depict resistance activity in Europe by showing the Bomasch’s refusing to be part of the German war machine and their attempts to get to safety in Britain. The American government originally refused to allow the film, titled Night Train for US audiences, to be released in the USA until it was drastically cut in order to avoid giving the impression that England was overrun by traitors – the ease of Marsen entering Britain, his secret contact at the opticians and the equally ease of the U-boat entering British waters. It was however, a British Ministry of Information honorary advisor, Sidney Bernstein, who agreed to the cut, much to the annoyance of the production team. In effect it was a great British propaganda coup in helping to convince the USA to join the allies in the war against Germany some two years later after Britain had declared war.

Running for 15 weeks in New York, the film was successful on either side of the Atlantic with and was popular with a wide range of audience types, including political leaders, film directors and leading actors of the time. Hedda Hopper, the influential Hollywood gossip columnist, wrote "At a neighborhood theater where it was showing the other night I saw six of our prominent directors and Bing Crosby, Spencer Tracy, Walter Pidgeon and Claudette Colbert in the audience. You know this is the picture of which Winston Churchill asked to have a special showing. If you miss it, don't say". Marlene Dietrich, Joe Pasternak and Alfred Hitchcock also went to see it.

Disappointingly, the film is very rarely screened which is why it is great news for Margaret Lockwood fans that in September 2016, Criterion released a Blu-ray edition of the film with a restored high-definition digital transfer This latest release offers a couple of additional features comprising a video conversation between film scholars Peter Evans and Bruce Babington about director Carol Reed, screenwriters Frank Launder and Sidney Gilliat, and the social and political climate in which Night Train to Munich was made plus an essay by film critic Philip Kemp

This blog has been written as part of the Margaret Lockwood Centennial Celebration, be sure to visit A Shroud of Thoughts to read more articles

RSS Feed

RSS Feed